September 2016 History Spotlight: The Belmar Campus

The King’s College campus in Belmar, New Jersey started life in 1914 as a 90-acre research and experimentation site for long-distance radio transmission under the pioneering supervision of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of the wireless.

The King’s College campus in Belmar, New Jersey started life in 1914 as a 90-acre research and experimentation site for long-distance radio transmission under the pioneering supervision of Guglielmo Marconi [1], inventor of the wireless. Marconi, the son of an Italian aristocrat and the granddaughter of John Jameson (a famous whiskey distiller), was the first to succeed at transatlantic radio communication. Before he achieved that milestone, he demonstrated that ships could communicate with each other at a significant distances by wireless. Wirelesses called “Marconi’s” then became standard issue on commercial ships that contributed to the rescue of 700 people from the wreck of the Titanic. Later, Marconi supervised the Pope’s first worldwide radio address.

The Belmar station consisted of a development laboratory, dormitories, and two residential houses, among other buildings. The U.S. Navy took it over during World War I for military communications, along with the New Brunswick, Canada station of the American Marconi Company.[3] Both facilities participated in broadcasting President Woodrow Wilson’s appeal to the German people to overthrow the Kaiser.

Marconi was widely acclaimed for his prowess. Italy made him a Marchese, or marquis, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics. Numerous American sites are named after him. He was a devout Roman Catholic and later a dedicated Italian fascist[4] —dying, however, in 1937 prior to the start of World War II. Perhaps the last thing he—or for that matter the U.S. Navy—could have imagined the property becoming was the residential campus of Percy Crawford’s “fundamental Christian college.”

Percy started praying about starting a Christian college sometime in 1932, after starting a course in Philadelphia called “The Young People’s Bible School.” It drew 200 students in its second year. “This Bible school work was so successful and so blessed of the Lord, and so many young people were coming for this training, that God laid it on my heart to start a regular school,” he said of the experience.[5]

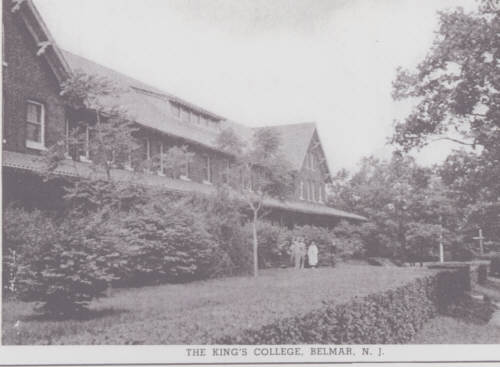

This idea too was so popular that Percy had to abandon his initial hope of locating the college in a building in New York or Philadelphia and look for a place that could house greater numbers. Percy was a radio pioneer in his own way, so when he found the Marconi property, it resonated with his work. The landscape, as later described by a student, was a mixture of “sand dunes and scrub pine.”[6] The August 1914 issue of Wireless Age describes something a bit more lush, highlighting “the spoils of wild grape vines and huckleberries, mulberries and blackberries;” sweeping views from the bluff on which the main building stood; and the area’s suitability for picnickers from summer cottages on the Jersey shore.[7] Percy negotiated to buy the property and buildings for $60,000 in the summer of 1936, and formed a board of trustees for the College’s parent organization—The Young People’s Association for the Propagation of the Gospel—which authorized loans and fundraising to pay for the campus.

If $60,000 sounds amazingly low in today’s dollars for ninety acres of East Coast, it was not much less amazing in those days; the Marconi Hotel alone had cost $265,000 to build.[8] What had happened to make the property so cheap was this: The American Marconi Company had had all of its shares bought out by a group of investors who dissolved the Marconi Company and incorporated themselves in 1920 as the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). RCA, then, owned of the Belmar property but was hampered in expanding operations there because of the price of land. The president of RCA jotted in his notebook, “What to do with the Belmar station?” In the end, they sold the property in the late 1920s and moved to Riverhead, Long Island, which is so remote that, in the words of Wall Township historian Fred Carl, “it is full of potato farms to this day.”[9] One can assume RCA was able to find all the space they needed.

The buyer of the Belmar property was another group of investors, who leased it out; but the tenant group was eventually evicted for not paying rent. By that time the Great Depression was in full force, and there was a court dispute between the owners and the tenants. In the end the property was transferred to a holding company or bank receiver, and it was during that financially fortuitous window that Percy Crawford came knocking.

Unconventionally, Percy had no big backers for his “Wheaton of the East”; Christian businessmen did not come forward to finance the venture. It’s possible Percy simply didn’t prioritize the intensive work of donor development because he felt such a deep urgency for evangelism; if he did try to recruit donors, Dan Crawford speculates that they may have felt there were holes in his administrative plan (which was to hire a trusted administrator to run the college, while simultaneously holding final authority and—at that stage—devoting most of his time to other work). Apart from loans, then, all fundraising was conducted through Percy’s radio ministry, the Young People’s Church of the Air. He hit his target on time. The King’s College opened on September 19, 1938, with 67 students and around ten faculty.[10]

King’s put all of the old Marconi buildings to use. The heat and power plant was converted for biology classes, and an addition was built for a gymnasium in the summer of 1938 before students arrived. The Marconi Operations Building became the science building. Another building of uncertain origin was used as a dormitory, as was an old farmhouse on the property where Marconi would formerly stay when he visited the station. And the Marconi Hotel, which was the largest on the property and formerly served the company’s operators and engineers,[11] was the college’s main building. Dining, chapel, social life, and some instruction took place there, and it was where the female students lived.[12]

A year into the brand-new school’s life, Percy and the King’s board and administration realized the College was not going to meet New Jersey’s accreditation requirement that four-year institutions have half a million dollars in an endowment. They tried to apply for two-year junior college accreditation instead, but there were financial obstacles to that plan as well, and it was abandoned in favor of the original model.

“It soon became apparent that King’s would have to relocate if it wanted to confer degrees on its first graduating class. Other religious leaders might have might have abandoned ship when faced with the daunting task of starting up again after only three years—especially at a time when the country was on the brink of war, but not Percy. He was getting close to fulfilling his vision of sending college-trained men and women into Christian service and never for a moment thought of giving it up. Board members began to make inquiries and found that the state of Delaware offered the most hopeful prospect, since it did not require an endowment and had less stringent degree-granting requirements. In fact the college would be able to confer degrees in its first year there, on the first graduating class of 1942.”[13]

The Belmar campus was sold to the U. S. government in 1941, but because Army also had a condemnation action on file, many a casual observer has assumed that the Army forced the College out. This was not the case. The Army was keen to buy the facility for radar development research. Its existing laboratory at Fort Hancock on Sandy Hook had been deemed too vulnerable to attacks or raids from German U-boats, and a team of Army surveyors was looking all down the Eastern Seaboard and Mississippi River for a securer location. When King’s put the Belmar property up for sale—close to Sandy Hook and sheltered as it was on an inland bay—it was rather perfect for the Army’s needs. But Fenton Duvall, Percy’s brother-in-law who taught history at King’s and served as registrar and main administrator, made clear to Mr. Carl that King’s was also eager to sell.[14]

King’s, of course, moved to New Castle, Delaware, which will be the subject of next month’s history spotlight. The Belmar property was renamed the Army Signal Corps Radar Laboratory—until American intelligence powers got wind that this name was essentially advertising the nature of a top-secret effort. Then it was renamed Camp Evans.[15][16]

The last military research project left Camp Evans around the year 2000. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002 and is open to the public. The Marconi Hotel, which was the center of the King’s campus, is now the InfoAge Science History Museum. Mr. Carl mentioned that alumni are warmly invited to visit the museum and the grounds to see where everything started, as well as to hold functions at the facilities there. Thanks to his efforts, the museum includes an exhibit about the early years of The King’s College.

From a quantitative perspective, The King’s College and Belmar, New Jersey are little more than a blip in each other’s stories. But that’s not how it works for an institution just getting off the ground. The effect of the Belmar years and the rapid transition to Delaware was to bond students tightly together. It was a time of wearing many hats, of frugal living, of closeness with faculty (perhaps particularly the young Fenton Duvall and his wife, Hannah), and of believing that God had a mission for King’s and its people. The Belmar years are also a study in God’s provision for King’s, in just the right way and at just the right time—when, as Dan Crawford noted above, others might have quit.

We will see that theme again.

[1] http://infoage.org/j/guglielmo-marconi

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sterling, Christopher H., ed. The Biographical Dictionary of American Radio. London: Routledge, 2010. Accessed via Google Books, September 8, 2016.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guglielmo_Marconi

[5] Crawford, Dan D. A Thirst for Souls: The Life of Evangelist Percy B. Crawford (1902-1960). Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 2010. P. 187.

[6] A Thirst for Souls, p. 196.

[7] Wireless Age, August 1914, accessed at http://www.campevans.org/_CE/html/vthotel.html#history, September 9, 2016.

[8] A Thirst for Souls, p. 187.

[9] The details about how the Belmar property changed hands in between the Marconi Company and The King’s College were supplied by Mr. Carl in a phone conversation on September 9, 2016.

[10] A Thirst for Souls, p. 190.

[11] “The history of the Marconi Hotel,” accessed at http://www.campevans.org/_CE/html/vthotel.html#history, September 9, 2016.

[12] “The King’s College.” Accessed at http://www.campevans.org/history/the-kings-college?showall=1&limitstart=, accessed September 9, 2016.

[13] A Thirst for Souls, p. 195.

[14] Footnote to The King’s College Silver Anniversary Supplement: “A Look Through the Years,” accessed at http://www.campevans.org/history/the-kings-college?showall=&start=5, September 9, 2016.

[15] Phone conversation with Mr. Fred Carl, September 9, 2016.

[16] Jared Pincin, Assistant Professor of Economics, notes that his grandfather was stationed at Camp Evans in the 1950s during the Korean War.