Political Violence in American History

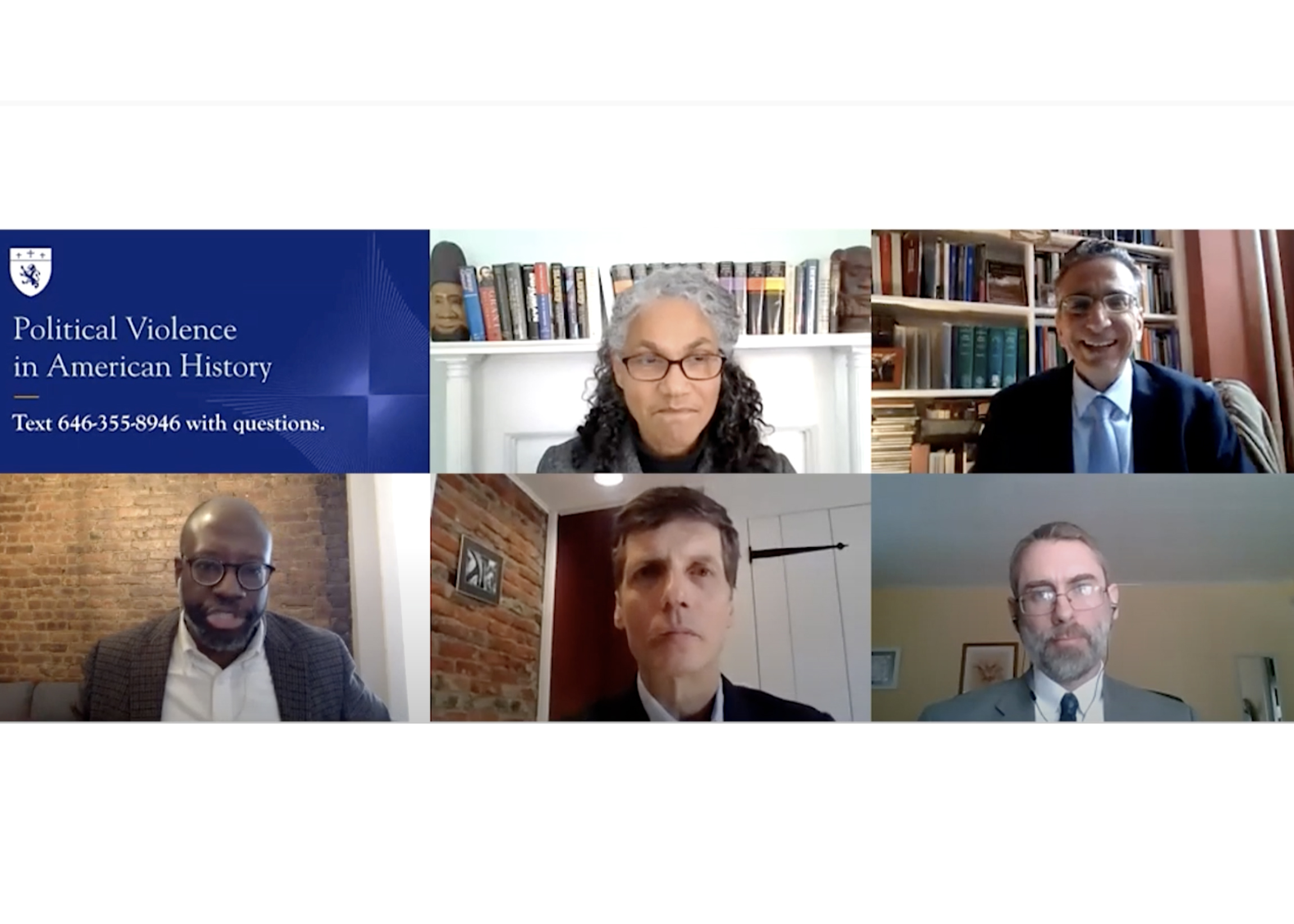

Dr. Jacqueline C. Rivers, Dr. Anthony Bradley, Dr. Matthew Parks, Dr. Joseph Loconte, and Dr. David Tubbs provided historical and scriptural insights about recent incidents of political violence.

On January 29, The King’s College hosted a panel discussion on “Political Violence in American History.”

Moderated by Dr. Jacqueline C. Rivers, senior fellow of the Center for the Study of Christianity and the Black Experience, the virtual event featured presentations from Dr. David Tubbs, Dr. Matthew Parks, Dr. Anthony Bradley, and Dr. Joseph Loconte. The purpose of the event was to offer “historical and scriptural insights about the political violence we are witnessing today to better understand and respond to our current moment.”

WATCH: Full panelist presentations and Q&A

After an introduction by President Tim Gibson, Rivers delivered opening remarks. She contextualized the day’s discussion of violence within the United States’ history with domestic terrorism, particularly against Black Americans. She also noted the continuing threat posed by white supremacist extremists in the United States, citing an October 2020 Department of Homeland Security report that catalogued “racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists—specifically white supremacist extremists” as the “most persistent and lethal threat in the Homeland.” She argued that these dangers are intensified by echo chambers in social media and cable news, and urged listeners to “diversify our sources of information” to counteract the tide of polarization.

Associate Professor of Politics Dr. David Tubbs discussed the relationship between freedom of speech protections and threats of violence. In the traditional view, based on the social contract theory of thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, a properly instituted government holds a monopoly on force. Open advocacy of violence goes against the purpose of the state, and is therefore not protected by the law. In the United States, this evolved into a doctrine of “true threats.” The “true threat” model states that the government cannot prosecute threats of violence unless those threats are serious from the standpoint of a reasonable person: speech must be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The theory was put forward in Brandenburg vs. Ohio (1969), when the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a KKK member who threatened “revengeance.” He ended his presentation by connecting these cases to discussion of the January 6 attack on the Capitol.

Associate Professor of Politics Dr. Matthew Parks recounted the history of the Whiskey Rebellion, sharing the steps George Washington took to reduce partisanship and minimize violence. When Congress instituted a tax on whiskey to pay down the war debt in 1791, citizens began to evade the new tax. In 1794, a mob in Western Pennsylvania attacked a local tax collector, John Neville, in his home. Hamilton wanted the full force of the law to be brought against the offenders, while Washington feared that any military response would only “confirm the wildest fears about military despotism” that the Anti-Federalists had raised. Instead of immediately deploying troops, Washington met with the Pennsylvania governor to determine a response and ordered the mob to disperse by a set date, suggesting that he would offer clemency to those who did. When the militia did march, they were met with no armed resistance. The unpopular law was eventually addressed through legislative means when Congress repealed the whiskey tax.

Professor of Religious and Theological Studies Dr. Anthony Bradley spoke on “the strange nonviolence of the Jim Crow era.” Between the years of 1880 and 1968, about five thousand Black Americans were lynched. While lynch mobs also targeted lower-class whites, lynching was primarily “a means to introduce intimidation and fear to restrict the economic and political liberties of Blacks,” said Bradley. White Americans committed domestic terrorism against Black Americans in Mississippi, Georgia, Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, and North Carolina. This violence was not limited to rural areas. Bradley cited numerous examples of white men and boys inciting riots and committing arson against Black Americans in cities such as Atlanta, St. Louis, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. Some of the worst violence took place in 1919 as white soldiers returning from World War I found that their jobs were now filled by Blacks. Yet “the Black response to violence was categorically non-violent,” Bradley said, taking the form of boycotts, the creation of organizations like the NAACP, and developing and improving segregated facilities. These efforts eventually gave birth to the Civil Rights Movement and the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Senior Fellow in Christianity and Culture Dr. Joseph Loconte discussed 1968, a year characterized by a “sense of distrust of political and educational elites” across party lines connected to both the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war movement. While there had been gains for African Americans, such as the Civil Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act, issues of police brutality, poverty, and lack of access to education remained. “There’s a profound impatience with the pace of change,” Loconte explained, “So the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968 sets off a tinderbox.” Riots, looting, and arson occurred in almost 200 cities in the days following the assassination. Loconte also detailed the August 1968 protests during the Democratic National Convention, when police brutalized protestors. He argued that this indiscriminate response accelerated the erosion of trust in public leaders. Loconte drew several lessons from the events of 1968: that leaders “speak into the causes of social unrest without partisan rancor,” that we identify and delegitimize the violent movements that attach themselves to political parties, and that we navigate between cynicism and utopianism.

The Q&A period touched on violence toward indigenous people and to what extent Black Lives Matter and Antifa were responsible for inciting violence in recent protests. A recurring theme in the discussion was on the kind of practices necessary to seek the common good.

Loconte: “One of the ways that we demonstrate the love of Christ in the public square is that we are honest brokers. Speaking truth into the situation in an even-handed, non-partisan way seems to be one of the great needs of the hour. I’m thinking of the 16th and 17th century, with the religious violence between Catholics and Protestants: Jacob Aconteus, a Protestant, wrote a tract going after both the Catholics and the Protestants engaged in a religious, sectarian war. He was willing to call out both sides.”

Bradley: “Christians need to consider the invitation of not identifying their primary allegiance as to a political identity. You cannot say, ‘I’m a Christian, therefore I’m a Democrat’ or ‘Because I’m a Christian, therefore I’m a Republican.’ All of these ideologies tend toward idolatry. They all promise things in a gnostic way, they promise to provide a salvation story of public policy that can never deliver what it promises.”

Parks: “We are very good at pointing out the speck in the eyes of everybody else and of course we have this massive log protruding from our own eye. We can learn from these historical examples, where we see efforts to appreciate points of commonality. One of the things Washington did well was to isolate those who were committed to violence from this other group that got swept up in it.”

Tubbs: “When we tell the history of the United States, we must acknowledge the gap between ideals and reality; ideals and institutions are going to fall short of our expectations of them, but ideals must be part of the story. The ideals of the American Founding are noble ideals and we’ve been aspiring to reach those ideals for all of our history.”